Lee Sharpe looks at the several redeeming features behind the CGT regime and particularly Only/Main Residence Relief, any of which may yet swoop to defend a besieged Member of Parliament.

Introduction

Nearly a quarter-century ago, I watched a political thriller called “The Contender”. The plot oriented around a fictional US vice-presidential candidate being accused of having had an eventful social life in her college years that, had she been a man, would have comprised an advertisement, not a drama. But she wasn’t, so… well, you can guess. I cannot remember the name of the lead actress but if I remember correctly, she smashed it. The tension between doing the easy thing of just addressing the prurient/puerile questions, and the hard thing of holding up a quiet mirror to the double standards, was memorable. Just not memorable enough for me to remember her name, obviously.

They do say that a week is a long time in politics, so I am delighted that we can all pat ourselves on the back that, some 1,200+ such long-times later, sexual double-standards are a thing of the past. But we still need some kind of scandal, so thanks be to Ms Angela Rayner for giving us something tax-ish, if not particularly taxing.

Apparently, there is grave concern in some quarters that Ms Rayner may have understated her personal tax exposure, by claiming 100% CGT relief on the sale of her former, allegedly part-time home, back in 2015. The tax at stake may run to as much as “4 figures”, so a decent lunch for some but, be assured, there are principles at stake here. And such is the spirit in which we shall deal with this issue.

To be honest, I am surprised that this non-story is still a story. In fact, it appears to have grown legs. It seems only a few weeks ago that I was forced to put metaphorical pen to paper over the whole sordid “tax on eBay ‘trading’ “ affair that, again, should not have been an issue but for the dullards, drones and duncissimi who infest the general press. Ah, yes: people who say they “side-hustle”; “influencers”; and those who think the word “multiple” sounds impressive – truly a Venn diagram for our times.

(Some readers may be relieved that my earlier effort never made it out into the wild as, having finally coalesced around a rather nifty flow-chart, I discovered that LITRG had handsomely beaten me to it. As veteran readers will know, we at TW have long held a soft spot for LITRG, harking back to halcyon/Williamson days. Hence, we shelved our masterpiece, so as not to crowd the bandwidth. Of course ours was better, given that we covered the money’s worth principle, and funnier, because we had a section dedicated to explaining why “handbags and shoes are almost never an investment, from a tax perspective, despite what some may say” and anyone daft enough to admit to being an “influencer” on our flow-chart might have found death, or even ex-communication*, preferable – to me, at least – over taxes. But, as usual, I digress).

Anyhew, let’s have a look at the many reasons why the MP taxpayer in this particular scenario may well be on the right side of the law, if not – for now, at least – on the right side of the floor.

For the avoidance of doubt, the article deals only with such matters as have been reported widely in the press. No special knowledge is claimed, other than perhaps in relation to tax itself. The principles here orient around Principal Private Residence (PPR) Relief, also known as Only or Main Residence Relief. The article will use PPR as shorthand/abbreviation, except when I get bored.

The legislation behind PPR Relief itself resides at TCGA 1992 ss 222 – 226 (now 226B, thanks to much tinkering by the Government in 2019/2020 – FA 2020 s 24). We refer a fair bit to CGT legislation, PPR case law and HMRC’s guidance.

In particular, I do not comment on the non-tax implications of the taxpayer’s reported circumstances.

Facts and Rumour in the Public Domain

- Ms Rayner (“the taxpayer”) acquired her only home (at that time) in January 2007 in Vicarage Road in Stockport, for £79,000.

- She married in September 2010. This is quite relevant for CGT purposes. Just not in the way that most people reporting on this case seem to understand.

- The children whom the taxpayer parented with her husband were apparently “registered” at her husband’s pre-matrimonial home in Lowndes Lane from October 2010. (This is potentially relevant.)

- It has been reported that the taxpayer’s sibling may have occupied her Vicarage Road property between 2010 and its disposal in 2015. Some commentators seem to think that this damages the taxpayer’s position. I disagree that this likely damages the taxpayer’s position (at least, from a tax perspective). Lettings Relief was alive and kicking in 2015, and the established practice for lodgers in one’s main home, that broadly ran in parallel therewith, was also in rude health. (The precise circumstances of the principal taxpayer’s ownership / occupation would be pivotal, as regards those treatments. But there are other possibilities.)

- She sold the property in March 2015 for £127,500. I have assumed that this sale was to a third party, such that the sale price as recorded/reported will correspond with the gross proceeds for CGT purposes.

- Apparently, Ms Rayner is adamant that the Vicarage Road was her main residence throughout. Newsflash: according to tax law, this is perfectly plausible, no matter what the neighbours supposedly say.

- We do not actually need to know her other income or taxable earnings, unless we fail in our quest and the taxpayer ends up with some net taxable capital gain. And we shall not fail, because reputations are at stake (not hers, mine, such as it is).

Setting the Scene

- I am assuming that the taxpayer was resident in the UK for CGT purposes throughout the relevant period (and domiciled within the UK, for that matter). If not tax-resident, then a sale of their UK property could have escaped CGT entirely, as a disposal made prior to 6 April 2015.

- Also, that the taxpayer had made no capital losses in the tax year or prior, that might then be used against any otherwise-unrelieved gain on the property.

- That it was the freehold in the property that was bought in 2007 and sold in 2015, for simplicity

- Finally that, some time after it had ceased to be her main residence, the taxpayer did not avail herself of TCGA 92 s 222 (7) in relation to the Vicarage Road property – as that provision applied in 2015 and for more than 40 years** before the Government of 2020 decided it had a better appreciation of how its elders and betters had intended for the legislation to work. Given the timings involved, such manoeuvre by the taxpayer seems unlikely, albeit far from impossible.

Note that the foregoing assumptions largely work to the detriment of the taxpayer, not to her advantage. I like a challenge.

I think that most people will be working on the basis that the taxpayer will have lived in the Vicarage Road property as her main home, at least for a few years, since its acquisition. The usual key condition – that, in order to secure any measure of PPR Relief, the property must have been occupied as their PPR at some point in their period of ownership – appears to have been secured, broadly from the outset of ownership. PPR Relief is therefore in play: it is more that the proportion of gain that is eligible for PPR is under scrutiny.

I suppose some might wonder if, having made a home at Victoria Road, the taxpayer needed for it to be her main residence if, for example, they spent a lot of time elsewhere. By my reckoning, it could have been her least-favourite place to live from purchase in January 2007 right up until at least marriage and this would typically not matter: if she had a “CGT’able interest” in only one property and that property were at any stage occupied as their residence, then it would still qualify as their only residence, or PPR, for CGT purposes, even if they did live mostly elsewhere – friends, relatives, etc. It should not be difficult to see that this is logical, in line with standard interpretation, and likely saves a substantial proportion of ordinary taxpayers with busy and varied social lives. There is a risk if there were formally-rented tenancies knocking around at this point, but there should also be a remedy***

The issue that seems to be causing some people so much concern appears to be the period from marriage to sale: was it her main residence throughout her ownership to date of sale or did she really live elsewhere, such as at her husband’s Lowndes Lane residence, so that a meaningful chunk of the 100% PPR Relief should be denied?

Basic calculation: Banking PPR to Date of Marriage

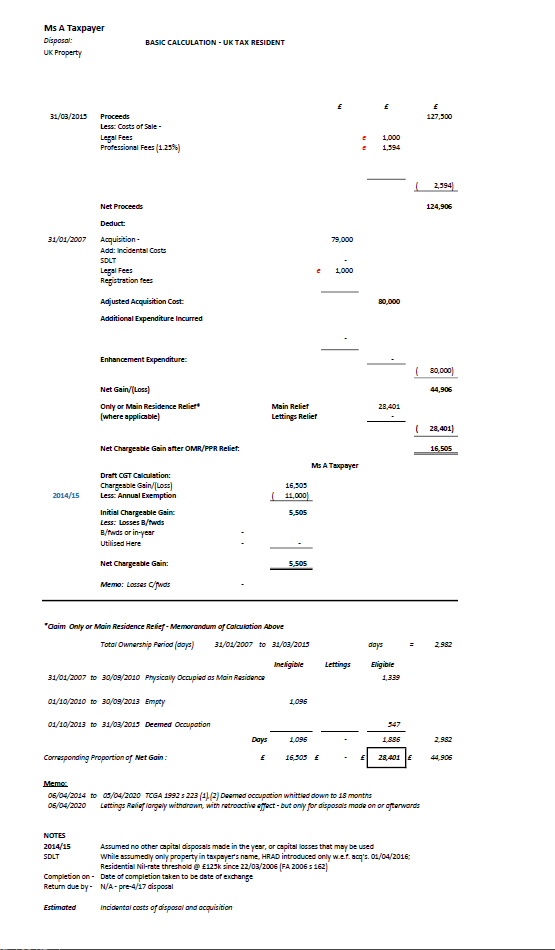

The following calculation assumes that the taxpayer will have qualified for PPR on the Vicarage Road property up to marriage in September 2010, but was not occupied by her as her main residence from that date onwards. This seems to be a very common assumption as reported by the press.

The basic calculation shows that the taxpayer’s gross gain is in the region of £45,000 but, after apportioning for the periods – plural (see next) – for which she will almost certainly have been eligible for PPR relief, the net gain will be in region of £16,505, and after her 2014/15 Annual Exemption of £11,000, the net taxable gain will be just c£5,500.

The modest scale of the gain means that the Annual Exemption actually has quite a meaningful role to play here – the taxpayer should perhaps think herself lucky at this stage that her gain did not arise a decade later in March 2025, when the Annual Exemption, in defiance of inflation and basically all sense and reason, has been slashed to just £3,000.

Final Period of Deemed Occupation

In 2015, the taxpayer’s last 18 months’ ownership will automatically have been treated as eligible for PPR, regardless of how she actually occupied the property (including if she never set foot in the property at all in that final period). This is in the legislation and almost impossible to displace, as it was meant to protect people in all kinds of situations, who had moved house but were struggling to sell their former home (the grace period is only 9 months now, having been cut again in 2020).

So, now we know what we have almost certainly banked so far, let's turn to what other aspects may well act, alone or in combination, to further reduce CGT exposure to £nil.

Curious Angel #1 – Improvements to the Property

It is not difficult to see that a reasonable amount of post-acquisition capital expenditure on the Vicarage Road property will boost the costs deductible from the gain. A key issue is what actually counts as “capital expenditure” in this context. But that expenditure does not have to be just c£5,500, as it is vitiated or diluted by the PPR Relief already given. The qualifying capital expenditure would have to be in the region of £15,000, in order to work through to reduce the post-PPR-Relief gain to a point where it is entirely offset by the taxpayer’s 2014/15 Annual Exemption of £11,000.

I think I have read elsewhere the suggestion that this approximates to a new kitchen and a bathroom or similar. But, in my opinion, that is a quite dangerous assumption to make.

In most cases, replacing kitchens or bathrooms to a broadly similar standard as the original (compared to when those original fittings, etc., were newly installed) amounts to a repair. Mere repairs or maintenance of assets are not allowable for CGT purposes. We are not dealing with an annual incomes business here, but a long-term investment and the regime is quite different in such respects.

Nor is it enough to demonstrate improvement on the basis that the kitchen, bathroom etc., was pretty grotty when you moved in: you have to be able to prove that the underlying quality of the new kitchen, etc., is superior to what was there beforehand, so as consequently to enhance the property’s intrinsic value. Not impossible but, in my experience, quite unusual.

It is much easier to demonstrate that the overall asset – the land/property – has been enhanced where you are adding to the property – say an extra bedroom, attic room, conservatory or a bigger kitchen than was there beforehand.

But even that is not enough on its own. The expenditure then also has to be “reflected” in the asset at the time of disposal (TCGA 92 s 38 (1)(b)). Broadly, this means that the enhancement has still to exist in the property at the point of sale. So, adding a conservatory could be an enhancement, but not if it has been pulled down prior to the property’s disposal. Happily, if your conservatory really was dire, then its demolition could be said to have enhanced the property, meaning the costs of demolition, etc., might actually be …enhancements – see CG15200.

In a similar vein, if the taxpayer had ended up in a legal tussle over her ownership of the property, then the costs incurred would usually also count towards enhancement expenditure, deductible on sale, etc. (It might not enhance the value of the asset itself, but it has gone to improve the merit/value of the interest she held, and would at some stage subsequently dispose of).

Curious Angel #2 – Nominating the Property

It has been widely reported that, after she married, the taxpayer was in fact living at her spouse’s pre-matrimonial home at Lowndes Lane. The implication offered is that Vicarage Road could not qualify as her main residence while she lived predominantly at Lowndes Lane. This may seem logical but it is not correct. A taxpayer has a window of opportunity to nominate which of their available residences is their main residence. However, this must sometimes be a joint nomination, where a couple is married / in civil partnership.

Whenever a taxpayer has a new combination of residences available for their occupation, then they are able to nominate which is their main residence. So, if one owns a holiday home in Scotland, and a usual abode in sunny Stockport, and then buys a pied-a-terre in Manchester city centre, they are allowed to nominate the holiday home in Scotland as their main residence, even if they only spend a few weeks or so there each year: it is their Scottish residence, or where they live when they are in Scotland. It does not matter that the Mancunian property is the new available residence: they can choose any from those available to them at the time. (Note that formally letting out properties on a long-term basis may well complicate this simple scenario).

The logic is to allow someone to protect entitlement to relief, even if their circumstances require them to adopt a temporary residence elsewhere (see also ***). But note that if I nominate another residence, I forfeit that protection on the first property (although I can nominate back later on, assuming the first such election has been validly made).

Buying another property is not enough: your “residence” must amount to somewhere that you can call “home”. But Lord Denning confirmed in Levene v HMRC [1928] AC 217 that someone may have more than one residence at a time, even if the law says one cannot choose to have more than one main residence.

The nomination window is usually 2 years from a new combination of residences becoming available. Spouses who are living together can nominate only one main residence between them, and in such circumstances that nomination must be made jointly. If such a nomination is not made, or not made in time, then HMRC will decide which is the main residence, based on the facts of the actual occupation of all of the available residences. So, in the absence of a valid nomination, various factors, such as where the children lived, etc., Council Tax, utility bills, where the parents worked, etc., would come into play. Hence it is indeed relevant where the taxpayer’s children may or may not have spent their time. Although it is fascinating that such careful research into the particulars of this case did not extend to the many and varied reasons why it is likely a non-event for tax purposes. Planks and motes, I guess.

It seems plausible that the date of marriage will have triggered a new nomination window (see, for example, CG64525). And it would have been entirely legal and quite common for, say, the new couple to have nominated Vicarage Road as their main residence, even if they subsequently spent the majority of their time at Lowndes Lane – particularly if they thought it likely that Vicarage Road would be sold before Lowndes Lane.

I mentioned earlier that there is some question over whether the taxpayer’s adult sibling may have lived in the Vicarage Road property for a meaningful period, after the taxpayer married. It is in my opinion plausible that the property could have remained a residence available for the couple’s occupation even so. Note that (now-)HMRC’s Statement of Practice 14/80 allows that a lodger may “live as part of the family” without risking any PPR relief; in this scenario we have someone who is a part of the family.

I realise that HMRC has subsequently argued at PIM4001 that Rent-a-Room Relief is available only to a lodger in one’s “main residence”, which in that context is determined on the facts of occupation and irrespective of any CGT nomination. That is fine: Rent-a-Room is an Income Tax regime, while SP14/80 was literally devised as an adjunct to what became TCGA 92 s 223(4) – Lettings Relief – as applied in 2015.

Antepenultimately, I am not sure how many rooms were at the property at Vicarage Road. It may not have been many, but it might have been adequate to cater for a lodger, even so. I do recall that my first home was a 2-bedder in Stockport, and I managed to squeeze 2 computer desks and a 6-seater dining table in the attic. I did not realise how “impressive” that was, until I had to get the thing out of there when we moved house again. Let’s just say that if I did that move today, the new owners would be getting a free dining table in their attic. That attic tried to kill me even before we moved in – much to my wife’s amusement, even now – and it damn near succeeded the night before we moved out. But I digress. Again.

Penultimately, I have read elsewhere that some think it unlikely that the taxpayer(s) will have made such a nomination, “in the circumstances”. While it is likely only HMRC that will know the truth of whether a valid nomination has been lodged, The public commentary may be sub-text for their presumed level of financial sophistication.

Now, if those subscribing to such a view are doing so because the taxpayer is from Stockport then I would wholeheartedly concur that most Stopfordians are indeed as thick as mince and furthermore, tend to have a massive chip on both shoulders about not really being Mancunians****. But I also find most people tend to sharpen up quite nicely when real money is at stake, and there was plenty of information about PPR nominations available on the Internet, even way back in 2015.

And, even if there were no such nomination and HMRC had to decide which was the main residence based on the facts, its officers know well enough that simply comparing days spent in each property is not enough:

“If someone lives in two houses the question, which does he use as the principal or more important one, cannot be determined solely by reference to the way in which he divides his time between the two.” Frost v Feltham Ch D [1980] 55 TC 10 – CG64545. (I do rather look forward to hearing from some reporter at the Daily Flail whether Mrs. Bucket from No. 32, in her considered opinion, reckons the taxpayer’s heating bills were higher at Lowndes Lane than at Vicarage Road).

Finally, if wannabe tax experts are feeling a bit put out, struggling with nominations, residences and main residences, then they might take comfort from Ellis v HMRC [2013] UKFTT 775 (TC), in which HMRC literally tried to argue in court that, while it accepted the taxpayer had validly nominated their main residence, and had occupied the proeprty as a residence, the taxpayer’s pattern of occupation of that residence was not quite enough to make it their… main… residence. To add to HMRC’s embarrassment, it was another case heard by Geraint Jones, KC. There was a time when he just seemed to cop for all the procedural howlers going. But that one in particular makes me chuckle, even now.

Curious Angel #3 – Marriage is Not (Quite) Enough

Maybe it’s just me, but something that appears to have been largely overlooked in the reporting I have seen is that the constraints on having more than one main residence and nominations, etc., by reason of marriage, apply only where the spouses or civil partners are “living together”. The phrase “living together” may not mean the same thing to everyone. Helpfully, (or not), the CGT legislation says at TCGA s 288 (3) that it means exactly what it says at ITA 2007 s 1011.

Simply put, this boils down to CGT law assuming that the spouses in a married couple (or civil partnership) are living together unless they are formally separated, or where they are in fact separated in circumstances in which the separation is likely to be permanent.

The turbulence in a marriage is not really a matter for public consumption or speculation, (It’s certainly not my business), but I suggest that it is far from impossible that a hypothetical taxpayer and their spouse could have separated on what at the time might reasonably have seemed to be a permanent basis, but later reconciled. Mathematically, in this particular scenario, a period of re-occupation of the former main residence at Vicarage Road for almost exactly a year might serve to reduce the CGT liability to £nil. Again, I am not suggesting that this is a likely reason, but that it is a possibility that should not be discounted. It might be sufficiently unusual that I expect that HMRC would either have been told at the time, or that there would be very good historical evidence to present now. To HMRC, not the public.

Curious Angel #4 – Exploiting Joint Ownership in the Couple

We do not know if the taxpayer set out to transfer any proportion of the Vicarage Road property to her husband upon or after marriage. HMRC might have known at the time, perhaps depending on the SDLT reporting on the transfer (if any reporting were required). In terms of a paper trail in the public domain, I do not think that legal ownership would necessarily be disturbed by a change in beneficial ownership between spouses. Transferring a one-third share to the spouse would suffice to move across enough of the gain on later disposal to the husband, that their combined Annual Exemptions in 2014/15 when Vicarage Road was sold on, would be utilised sufficiently to reduce the overall taxable gain to nil. (I am potentially leaning on TCGA 1992 s 222 (7), as noted in Setting the Schene above but this time I am assuming the more vanilla approach, when the transfer takes place while the property is the transferor’s qualifying main residence. The distinction no longer matters, after FA 2020 s 24.)

Most readers will be aware that the formal transfer of beneficial ownership of an asset may be wholly or partly executed between spouses, and between civil partners, who are living together as a couple, without triggering CGT. CGT on the asset’s subsequent sale is broadly taxable as normal. Again, not a tax ruse. (But the taxpayer may not have had to rely on the inter-spousal CGT provision, given the likely PPR-favoured status of the asset in question.)

Curious Angel #5 – Lettings Relief

The Lettings Relief facet of PPR Relief was largely neutered with effect for disposals on or after 6 April 2020. Although it is strictly still available, it is now much harder to meet the relevant criteria. Worse, the new test is applied to old periods, for disposals taking place now, including to older periods of letting that would have qualified at the time they arose in the overall period of ownership. Of course HMRC realised this when the 2020 change was introduced, but argued that it would be too complex to refine – one of the more outrageous “simplification” arguments we have seen from HMRC in the last few years. But for disposals back in 2015, Lettings Relief would have been roaming wild and carefree, like a Thomson’s gazelle. Or Bambi’s mum, early doors.

Depending on the nature of this supposed letting arrangement, it might again have taken only a year’s letting, to reduce the net taxable gain to £nil. HMRC argues that a letting must be on a commercial basis in order for the property to count as being wholly or partly “let as residential accommodation” – but that does not necessarily have to be in the form of money, as per CG4713:

“…if there was a genuine agreement to provide substantial services in return for the provision of the accommodation then this may be sufficient for [Lettings Relief] to be available [under TCGA92/S223 (4) as applied for disposals in 2015]”.

A warning that the value attributable to such hypothetical services may have been taxable as income, as and when it arose. It’s that money’s worth principle I mentioned much earlier, as set out in the classic case of Tennant v Smith [1892] AC 150. But if the supposed tenant actually “lived in the attic”, I am not sure how much that’s really worth, even in super-salubrious Stockport.

Curious Angel #6 – Beneficial Interest v Legal Title

It is reported that the taxpayer acquired the property at Vicarage Road for £79,000. This is presumably from Land Registry details – which, as anyone who uses them for real work knows, are not always accurate, particularly when the details go back a decade and more. Keep in mind that, pending the admittedly estimated incidental costs of buying and selling the property, the taxable gain is around £5,500.

Historically, the Land Registry has been primarily interested only in legal ownership – “title” – not the beneficial ownership that matters most for CGT purposes. It is also common for the historic details of legal title only partly to reflect the beneficial ownership (equitable interest) in a property. They are often one and the same, particularly when there is only one owner-buyer. But at TW we frequently encounter scenarios where close friends or family members contribute to the the owner-occupier's purchase price. Sometimes this is as a loan, where the co-contributor fundamentally seeks only the eventual return of their capital (and this is highly unlikely to be subject to CGT in relation to the property). In other cases, the co-contributor specifies an interest or return that is more suggestive of participation in the underlying asset itself – a beneficial interest in the property, where CGT would likely be in point for that secondary contributor. CG70230 has some useful indicators of whether someone has a beneficial interest subsiding in property.

Lately, I have encountered a few cases where HMRC has tried to argue that CGT does not, in fact, follow beneficial ownership and the disposal of a beneficial interest in the property. I disagree, (except to the quite limited extent that the disposal, etc, of a legal interest might itself give rise to proceeds that may then be subject to CGT). As do a number of court cases, I think, such as –

- Looney & Anor v HMRC [2018] UKFTT 619 (TC)

- Watson v HMRC [2014] UKFTT 613 (TC)

- Smallwood v HMRC [2006] EWHC 1653 (Ch)

So, on the assumption that beneficial ownership is indeed the defining metric, back to our taxpayer and the matter before us. Again, the actual CGT calculation itself demands considered attention but, broadly, our hypothetical co-owner would need to hold about a 1/3rd interest, in order for the first taxpayer’s net taxable gain to fall to c£Ni at final disposal of Vicarage Road in 2015. By my maths, it’s touch and go as to whether or not acquiring a 1/3rd share from the outset would result in a taxable gain for the second co-owner, when Vicarage Road was sold in 2015. But it almost certainly would not do so, if that co-owner were, say, also to occupy the Vicarage Road property as their main residence as well. Of course, I can really only be talking about the future husband here. Except that, actually, I am not.

Across the article so far, we have considered the possibility that ownership – by which I mean beneficial ownership – of the Vicarage Road property may have been transferred roughly at the point of marriage, or perhaps was shared at the point of acquiring Vicarage Road in 2007. But let’s suppose for an alternative scenario that the taxpayer bought 100% of the property in 2007, then decided to share beneficial ownership with another party, such as her sibling, say 2 years into her ownership of the property, early 2009.

Admittedly, there are a quite a few potential issues here:

- Usually, there are capital gains on almost all gifts from one individual to another – except for spouses and civil partners, as noted above. And it’s not because they may be siblings or other relatives either – although that certainly doesn’t help.

- It’s more to do with the fact that CGT legislation generally requires the donor to replace actual proceeds (if any) with fair market value, in their CGT calculation, whenever the donor intends an element of gift in favour of the donee (TCGTA 1992 ss 17,18).

- There are protections for, say, a discount on sale to a third party, or even an accidental/unwitting “bad bargain”. But not for gifts, etc., to connected parties such as siblings.

- There are also potential complications if the property is subject to a charge or mortgage, which may have something contractual to say about transfers – particularly to non-spouses/civil partners

- Not to mention the possibility of SDLT on the corresponding part-assumption of any mortgage debt or similar (assuming it was required or otherwise taken on) as deemed consideration (FA 2003 Sch 4 Para 8). I do not know if the property was mortgaged on acquisition but it is the norm. However, there is also a £40,000 de minimis, which might well suffice in this hypothetical scenario.

- (And there may be other, non-tax rules in play here, such as a restriction on onward participation or sale)

But if we assume that the Victoria Road property was in fact 100% the taxpayer’s PPR at least up to marriage in September 2010, then the taxpayer may have been able to transfer any proportion of her beneficial ownership in the property to anyone she liked, free of CGT at that point.

Again, rough maths and basic assumptions about the donee’s tax position in 2014/15 suggest that a 1/3rd share would reduce the theoretical net taxable gain for the taxpayer on final disposal to nil, likewise for the lucky donee, who would have picked up their interest in the property with a deemed CGT cost for them equivalent to the market value assessed on the donor – our taxpayer.

I am not suggesting the re-writing of events here. For example the application of proceeds – who got what, when sold – will usually be simple to verify.

The Devil in the Detail and a Headache for HMRC

Curious Angel #4 supposed that the taxpayer deliberately transferred a 1/3rd share of her 100% beneficial ownership of the Vicarage Road property

In fact, this co-ownership may have come about without conscious effort. For example, HMRC acknowledges at CG65310 that one spouse may end up having acquired an interest in the other’s property by dint of contribution to the purchase cost or subsequent mortgage contributions:

“It was held in [Hazell v Hazell [1972] 1 All ER 923] that if a spouse contributes directly or indirectly in money or money’s worth towards the initial cost, or towards mortgage instalments, they acquire, in equity, an interest in the matrimonial home proportional to those contributions.”

– and, while HMRC couches this primarily in the context of divorce and the matrimonial home, I am not sure that the courts would feel so constrained to recognise such interest materialising only on divorce, or only in relation to the matrimonial home – in fact later on, CG65310 also says that, where an agreement is reached, it should be accepted that such equitable interest arose from the outset. See also CG70230 in this regard.

While I profess no particular expertise in Trust or matrimonial law:

- Generally, the second individual claiming also to have a beneficial interest would have to be party to the proceedings at the beginning – when the property was acquired, etc.

- But if the courts were to decide that, however it came about, spouse B did accrue an interest at some point in property X, then I think HMRC would have to accept that was the case for tax purposes as well

I suspect that implied joint beneficial ownership may well go beyond mortgage contributions, etc., to the matrimonial home , and that conduct, use of the assets and how the proceeds of disposal were applied (such as to joint funds) might well also be indicative.

Clearly, such an approach would warrant careful consideration by Trust and property law specialists, although much may have been clarified in subsequent divorce proceedings (if there were any).

Lastly, to my eyes there is an interesting tension in the following assertions made by HMRC:

CG64525 sets out when a window for a new couple, etc., to nominate which of two or more residences is their PPR, and this explicitly includes where each spouse (or civil partner) has their own PPR before marriage, as would appear to be the scenario here – as a couple, they basically have to choose just one between them, or let HMRC decide for them later on, if necessary. So, immediately prior to marriage, each spouse has legal and beneficial ownership of only their own pre-matrimonial home.

Meanwhile, CG64470 says that an individual may nominate a property only if they have a legal or beneficial interest in that property. “Where an individual occupies their main residence [and they have no legal or beneficial interest in that property] but they also reside in another dwelling-house in which they have an interest, the residence in which they have an interest will be the only or main residence for private residence relief. This is because the word residence within s222 TCGA92 only refers to residences in which the individual owns an interest.” This is broadly echoed at CG64485, which says that an individual may nominate a property as a residence only if they have 2 or more residences in which they have a legal or beneficial interest.

So, how does Mr. Rayner get to participate in a joint nomination for Vicarage Road, in which he presumably had no interest; or Ms Rayner get to jointly nominate Lowndes Lane, assuming she likewise had no interest in that property? I don’t know if anyone actually made a nomination, but I should like to know how HMRC thinks one should approach the apparent conflict between CG64470 and CG64525.

HMRC might argue that it is only interpreting legislation; that the couple having to nominate only one residence between them is direct from that legislation and “statute is as statute says”; and that the statute has always been thus. But that would be to gloss over the fact that HMRC – or the Inland Revenue as it was back then – had a pretty serious re-think of the scope of that legislation in 1994.

Conclusion

This article has offered a veritable host of reasons as to why it would be wrong to suppose that something is amiss with this particular taxpayer’s tax affairs. A great many accountants and tax advisers know this (but have said little - and wisely so, I fear). Further, that a valid nomination for the Vicarage Road property could have made it the taxpayer’s main residence for CGT purposes irrespective of whether they spent significantly more time elsewhere. And even without a nomination, there is a sizeable basket of factors to consider before deciding which residence was the main residence, for a given period: it’s not simply a day-counting exercise.

When messing about with the numbers, the aim has been to get the net taxable gain – after any Annual Exemptions – down to £Nil, so that no CGT is actually due. Some readers might be concerned about whether tax returns should have been filed even so. While a taxpayer does have to file a return if they’re asked to do so, if HMRC doesn’t ask, then there is an issue only if there is a residual tax liability for that year. That is a very rude summary of TMA 1970 s 7. HMRC's practice is also quietly accepted in HMRC’s Enquiry Manual EM4552/5.

I am most grateful to our taxpayer-du-jour, Ms Rayner, for remaining tight-lipped about the whole affair. Not because it’s dignified or inspirational, like the aforementioned Contender, but because it’s given me a chance to finish the damn article first.

Finally, the actress in question was Joan Allen, because:

- I can Google, you know

- She was rather good, and

- Given how long this has taken, it would be rude not to

*I suppose incommunicado might be more apt, etymologically speaking, but given that a defining criterion of an influencer might well be that they would fervently profess that they “literally cannot live without my ‘phone”, I proffer that in similarly-benighted times, people feared excommunication by a capricious pope more than corporeal death itself… well, the parallel was too ‘nice’ to ignore.

**TCGA 92 s 222 (7) is a straight lift from at least as far back as CGTA 79 s 101 (7)

***This from HMRC’s CG64470:

“An individual’s only or main residence may be in a home in which they have no interest. Where an individual occupies their main residence under a licence but they also reside in another dwelling-house in which they have an interest, the residence in which they have an interest will be the only or main residence for private residence relief. This is because the word residence within s222 TCGA92 only refers to residences in which the individual owns an interest.”

Tax practitioners will realise that I use “CGT’able interest” to mean a dwelling-house (or part thereof) in which the taxpayer holds an interest whose disposal could be of consequence for CGT purposes. HMRC asserts that for the PPR regime, this includes both beneficial rights and legal rights under tenancy. Since October 1994, HMRC has accepted that this cannot include rights under licence – staying at an hotel, or with friends or relatives.

It follows that you might stay at a girlfriend’s or boyfriend’s house (etc.) 5 days a week as a matter of fact, but it will not be a residence, (nor can it be your main residence), for PPR purposes – unless there’s a formal rental agreement.

It also follows that, in theory, living in a rented property under a tenancy agreement can make a new residence for PPR purposes, and if you don’t make a main residence election then your other owned property could be at risk of losing favourable PPR status, because in the absence of an election, HMRC could determine that your rented property is in fact the main residence now eligible for PPR that is then wasted on a rental. Which is why we had ESC D21, now TCGA 92 s 222 (5A). This would likely cover our heroine for January 2007 to September 2010, which is all we need.

Some readers might argue that Yechiel v HMRC [2018] UKFTT 0683 (TC) undermines this approach, but it has not been reported that Ms Rayner lived in a nun’s cell in a house otherwise masquerading as a building site, so I think we’re probably safe. While some comments in Dutton Forshaw v HMRC [2015] UKFTT 478 (TC) are helpful, I am not sure the latter case is actually an antidote to Yechiel, given that there was no question of the latter property’s general suitability for, or restricted use while in, occupation.

****And I can say this because:

(a) I have lived here for a very long time, in case you hadn’t guessed

(b) And anyway, most Stopfordians can take a joke – those of us who can read, at least.

Please register or log in to add comments.

A thoughtful take on capital gains tax and tax redemption — definitely gives a fresh perspective. Helpful for investors and taxpayers alike. I often refer to Allenby Accountants when digging deeper into CGT matters.