TaxationWeb’s Lee Sharpe looks at a tenet, long-cherished by some, that lowering taxes – or lower tax rates – result in higher overall tax receipts.

Introduction

Advocates for a “low-tax regime” have often justified their position with the argument that lower tax rates encourage enterprise and thereby profits and, ultimately, higher tax receipts – “Laffer-lite”, if you will; laugh-out-loud, if you dare - some people take this proposition very seriously.

I have previously written at some length on the former Chancellor George Osborne’s cunning plan to make the UK competitive on the international stage, by progressively reducing our main Corporation Tax rate. This would supposedly encourage international business to move to the UK and establish profitable business here, so to increase overall tax yields.

History

Gideon’s Race to the Bottom started in 2010, with:

“Corporation tax rates are compared around the world, and low rates act as adverts for the countries that introduce them. Our current rate of 28 pence is looking less and less competitive. So we will do something about it.

Next year we will cut corporation tax by one per cent to 27 pence in the pound. The year after we will cut it again by one per cent. And again the year after, and again the year after that.

It will give us the lowest rate of any major Western economy, one of the lowest rates in the G20, and the lowest rate this country has ever know[n].”

Let’s see how this plan has panned… out:

Sources

Corporation Tax Statistics 2020 Table 11.1B (CT Liabilities)

The 2008 Recession: 10 Years On

Tax Statistics: An Overview 21/06/22

HMRC Tax Receipts and National Insurance Contributions for the UK (Annual Bulletin) 21/07/22

RPI = CHAW

Why Choose to Consider the Main Rate of Corporation Tax?

The vast majority of UK companies pay (and have historically paid) only the “small companies rate” or equivalent. But in fact the bulk of Corporation Tax is actually paid by the tiny minority of companies that make profits large enough to pay at the Main Rate (or would have done, under the old-but-soon-to-be-new-again regime).

For example, based on the Tables at 11.6 of Corporation Tax Statistics 2020, there were 1.11 million companies in the UK in 2013/14, liable for almost £40billion in Corporation Tax, in total. However, just 6,000 companies were responsible for £23billion of that – basically 58% of the tax take. By 2018/19, (the latest figures given), while there were significantly moe companies in existence overall, there were proportionately even fewer companies paying the lion's share of the tax. So, most Corporation Tax is actually paid at the Main Rate, even if it is paid by only a very small proportion of all of the companies out there.

Let's see how much Corporation Tax has been raised, as the Main Rate has fallen.

The Figures: Corporation Tax Rates v Liabilities 2000/01 to 2019/20

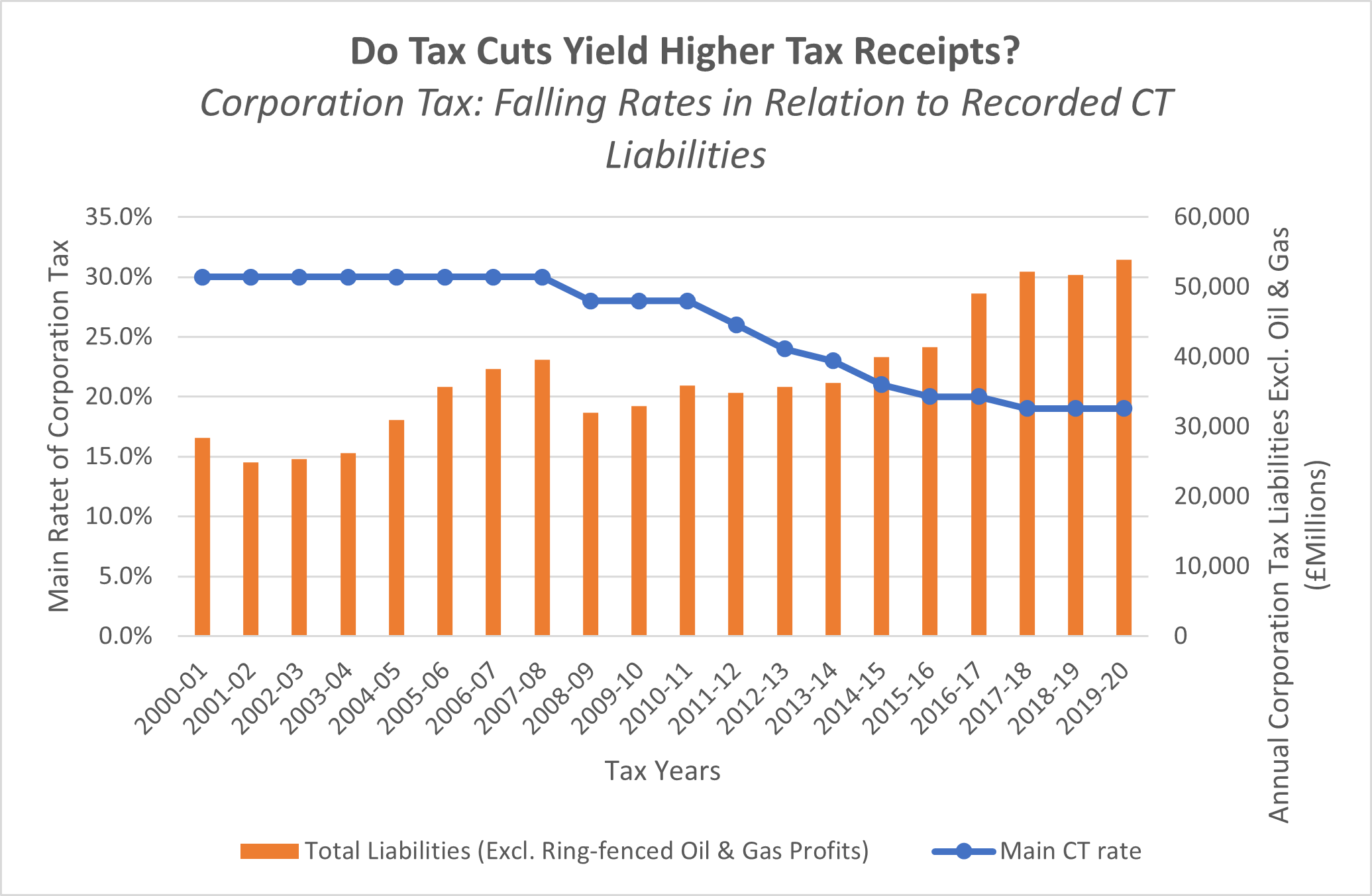

Based on the above chart, you might conclude that there is in fact some merit to the argument that a reduction in the Main Rate of Corporation Tax results in a higher tax yield. After all, considering the above chart, the tax take suffers an initial hit but then starts to increase soon after rates start to fall, and liabilities (excluding ring-fenced oil and gas companies) hit almost £54bn in 2019/20 – not far off double the total CT liabilities in the early ‘00s.

But this would ignore inflation. Simply, £54bn today was worth far less in 2001/02 (equivalent to saying something worth £20billion in 2001/02 would typically be worth much more than £20billion, today).

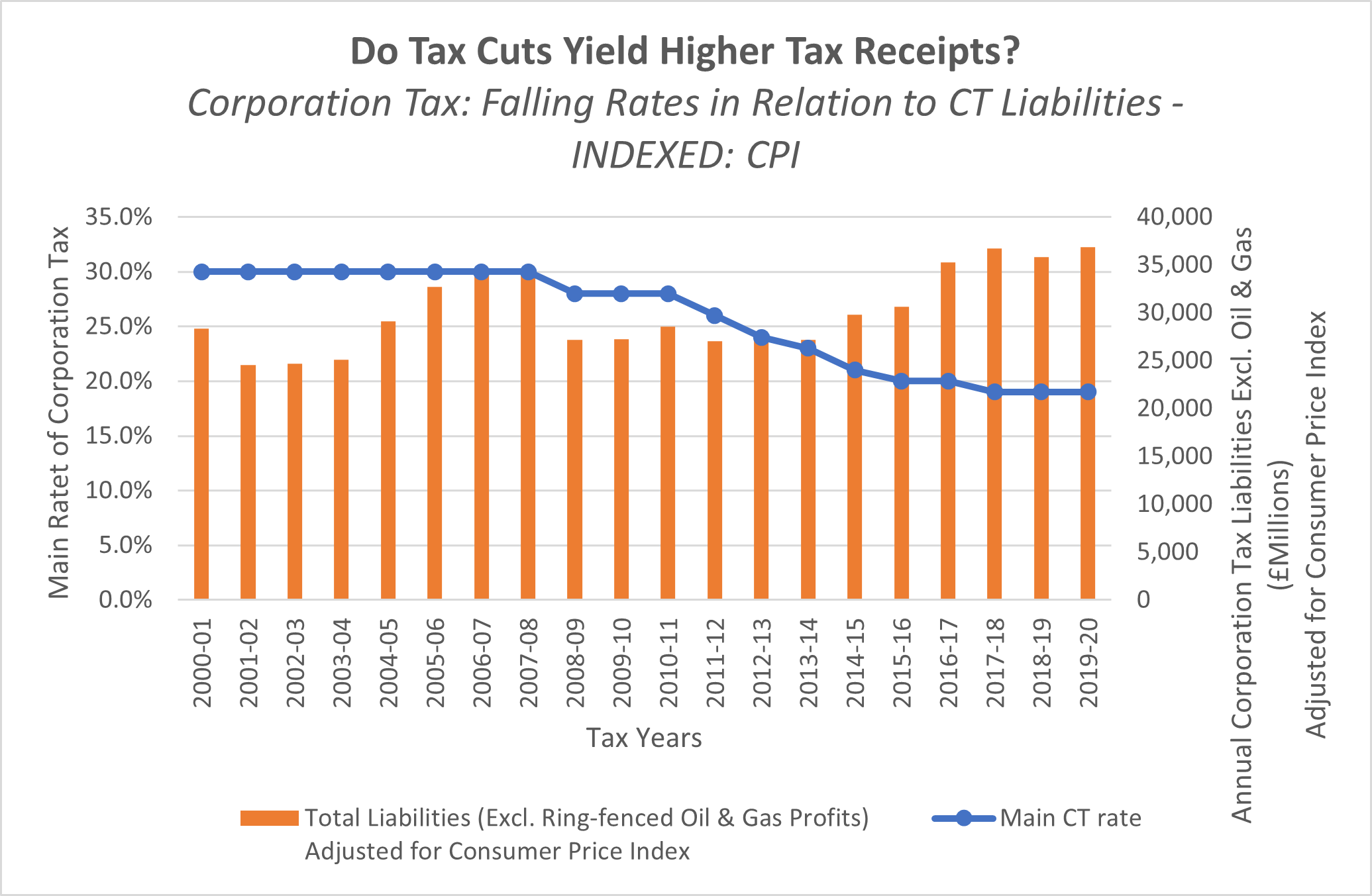

This is how the chart looks if we reduce all amounts to their 2000/01 equivalents, assuming the Consumer Price Index (CPIH) is an appropriate measure of inflation:

Recent receipts - as now indexed - are only a little higher than they were more than a decade ago. Note also that roughly £1bn - £2bn per year of the uptick from 2015/16 onwards will be attributable to the Bank Surcharge, introduced with effect from January 2016. Simply put, reducing the Main Rate of Corporation Tax has not 'unleashed' Corporation Tax take at all: Corporation Tax yield took a hit when the rates started to fall, and has taken roughly a decade to recover.

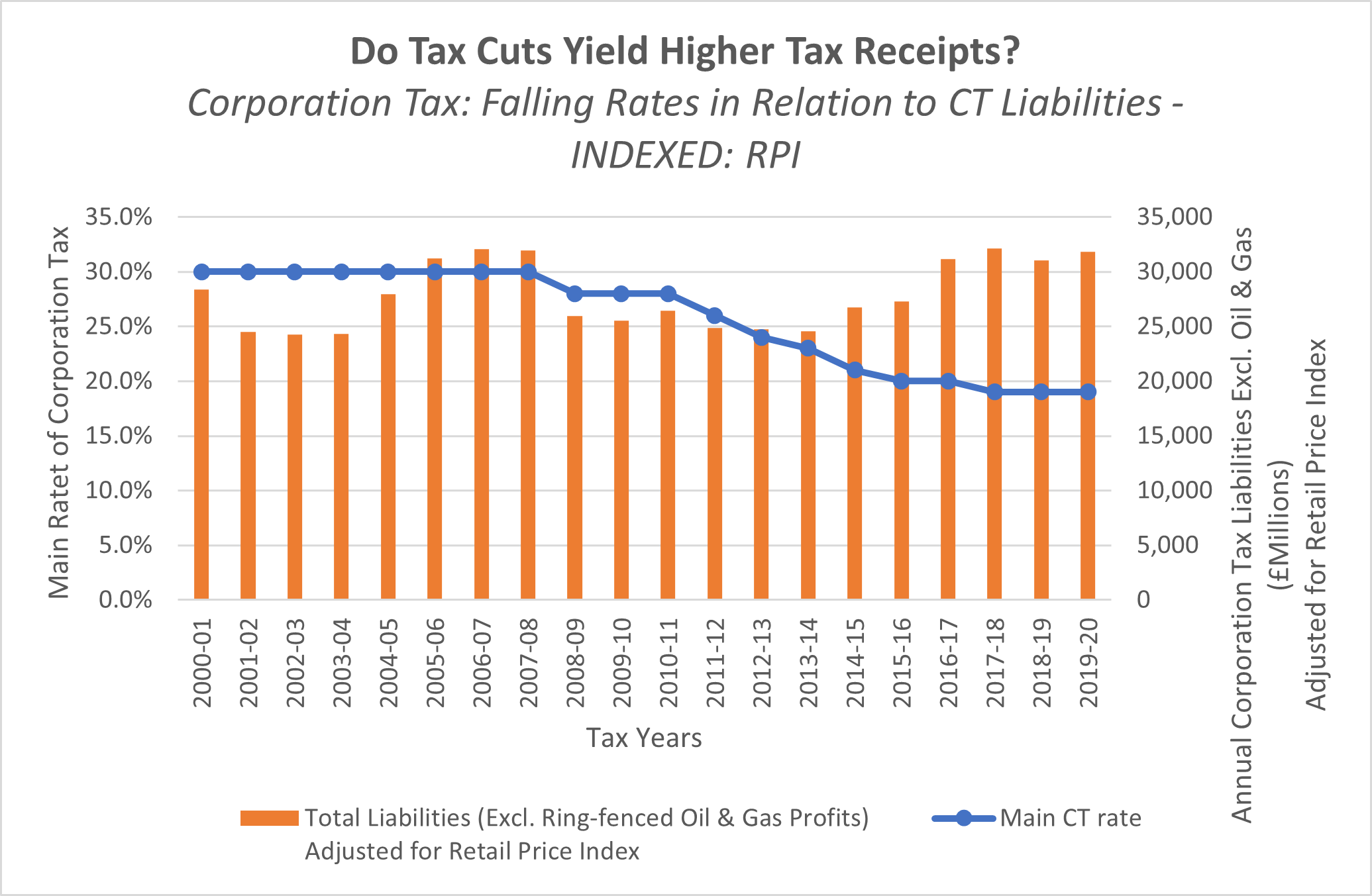

If instead we go all-out and resurrect the more volatile Retail Price Index (RPI), it looks even worse:

Using RPI, we are only now beginning to recover back to the levels last seen in the period 2005/06 – 2007/08 - just before the Main Rate of Corporation Tax started to fall. I have even resisted the urge to include oil and gas profits – which were large enough in the late ‘00s to make the last few years’ resurgence look quite anaemic, yet.

How About GDP?

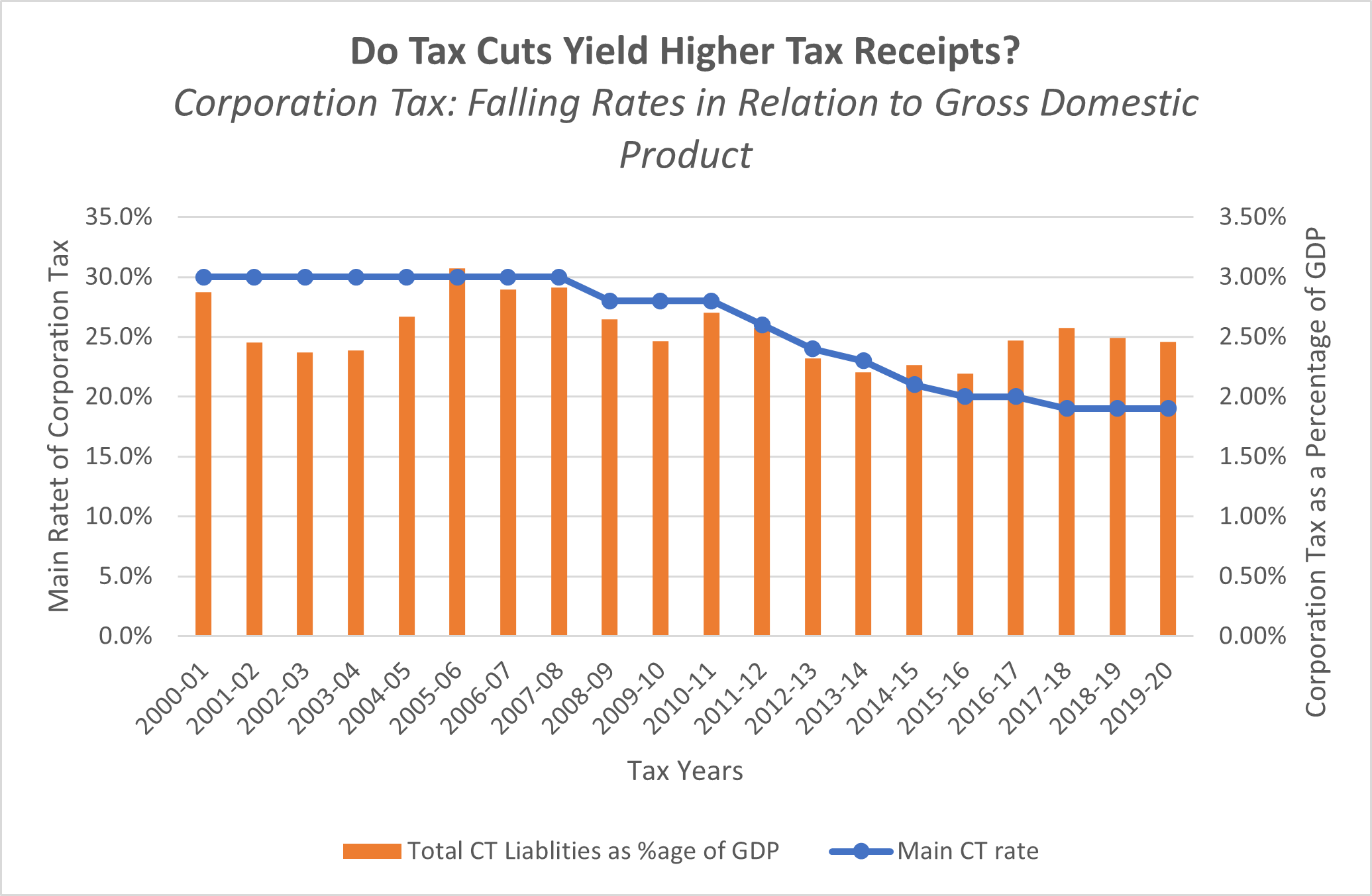

Another way to sideline any inflationary effect is to look at how much of a slice of the overall pie relates to Corporation Tax. In this context I have chosen Gross Domestic Product. If reducing the rate of Corporation Tax increases the relative contribution of Corporation Tax to GDP, then that might well indicate that lower rates glean a large slice of the overall pie, so:

Oh, dear. Here again, falling rates broadly coincide with reduced overall contribution. While contribution has regained some ground in the last few years, (again, thanks in part to the new Bank Surcharge), we are still some way below the level of the late ‘00s.

However:

- I have cheated by not excluding oil and gas profits this time, and

- I have lazily aligned the annual figure for GDP for the calendar year, with the CT contribution for the tax year.

In truth, I was just being lazy twice over. But I am too lazy even to correct my admission.

The broad finding would seem to be that cutting the Corporation Tax rate has had the effect of reducing Corporation Tax receipts, and that it could perhaps be argued that underlying Corporation Tax yield has increased slightly over the last decade or so since, despite cuts to the Main Rate, rather than because of them.

So, are there any reasons not to write off the “low-tax is best” charge of the not-so-bright brigade as faux-intellectual fopwittery of the lowest order?

Excuse #1: The Recession

Assuming we mean the Global Financial Crisis, as averse to either the COVID pandemic or the epic act of self-harm that durst not speak its name, (credit where credit’s due: we at TW were referring to it as “the Brexit omerta” mere days after the March 2021 Budget, which didn’t mention it even once), it might well be argued that the fall in CT liabilities around 2008/09 is more to do with the ensuing recession than with lower CT rates. But that would not explain why CT continued to slip against an all-incomes measure such as GDP (as above). Helpfully, the 2008 Recession: 10 Years On tells us that the UK economy had recovered to pre-GFC Recession levels by September 2013, while CT has still not recovered its pre-Recession contribution to GDP, almost a decade later.

Excuse #2: We Meant the Other Taxes

It could be argued that encouraging low-tax-seeking multinationals to the UK may not generate higher yields of Corporation Tax but it does (might) generate higher yields through PAYE Income Tax, NICs, etc.

There may be some merit to this, although it may be hard to explain why a low-tax-seeking business would be especially keen to make significant NI Contributions, etc.

This line of reasoning brings me neatly to one of my favourite self-owns in a Chancellor’s speech, being that from Summer 2015, extract as follows:

“Mr Deputy Speaker, we’ve cut Corporation Tax from 28% to 20% over the last Parliament, one of the biggest boosts British business has ever seen.

We can’t take it lower than that while such strong incentives are created for people to self-incorporate and pay the lower rates of tax due on dividends.

…

So I am today undertaking a major and long overdue reform to ‘simplify’ [by which of course I mean increase] the taxation of dividends.”

So, to paraphrase:

“My policy of reducing Corporation Tax rates to encourage businesses to come to the UK and post profits here, that will therefore boost tax receipts overall, has proved so spectacularly effective that tax receipts are in fact ...falling.

Despite this, I therefore need to double down on reducing Corporation Tax rates – seeing as how the policy has raised so much additional revenue so far – and encourage even more companies. Just not the British ones. To stabilise Income Tax receipts, I now need to lower Income Tax on dividends so that people are incentivised to make more profits to pay out as dividends and pay more Income Tax – no, wait, I am even confusing myself now – I need to say that I am reducing dividend income taxation, to lend credence to the mantra that lower taxes means more tax receipts, but actually increase dividend tax rates, because I have belatedly deduced that the way to raise tax yield is actually to …raise tax rates.”

- It is interesting to see a policy, that was openly devised originally in order to attract foreign companies, being passed off as a “boost to British business”

- As noted above. given that the vast majority of British companies had never paid the Main Rate of Corporation Tax, reducing it little by little over time had done nothing whatever to benefit them. Again, using the 2014/15 figures from Table 11.6 of Corporation Tax Statistics 2020, around 95% of companies would have been paying anywhere up to £60,000 in Corporation Tax (the maximum at the small profits rate of 20%, before the rates were harmonised). So, completely unaffected by changes to the Corporation Tax Main Rate, which only started to kick in once profits hit £300,000. Soon, however, they would all be paying significantly more Income Tax on their dividends! (Or the UK-resident shareholders of those 'small' family companies would be, at least.)

- The new dividend tax regime raised Income Tax rates on dividends, despite a manifesto pledge not to do so

- The increased dividend tax rates were forecast to start raising c£2bn a year in additional tax revenues, within a couple of years (line 16, Table 2.1, Summer Budget 2015). So that would be raising Income Tax rates, to increase tax revenues – while the Chancellor had previously set out to increase tax yield by reducing tax rates.

- Notwithstanding, international companies, and non-resident shareholders in receipt of dividends from the UK, were (and remain) largely immune to the increased rates of dividend taxation in the UK - because they basically pay no UK tax on UK dividend income anyway

- The net effect of these changes would be to try even harder to entice international companies to the UK, but further subsidised by British taxpayers/shareholders - thanks, George

“I Want to Believe” says Agent Scully Sunak – But Does He?

It seems that one of our more recent Chancellors, Mr. Sunak, has found himself declaring that a low-tax regime is the way forwards. Apparently, he has even pledged to cut the Basic Rate of Income Tax from 20% to 16%, but only once inflation and interest are under control, by the end of the next parliament – which could be as late as December 2029.

I therefore infer that Mr. Sunak does not subscribe to the dogma that simply lowering taxes will increase tax yield. Otherwise, he would have cut taxes all the sooner, to try to boost tax receipts.

In fact – and as we have previously pointed out – while he was Chancellor, Mr. Sunak appeared to be quite keen to basically reverse much of his recent predecessors’ tax policies, particularly:

- Proposing to reverse the cuts in Capital Allowances that have been made over the last few years

- Raising Corporation Tax rates (back) up to 25%, from 1 April 2023 (although that may well change, depending on who is chosen as the next Prime Minister).

One thing I still find remarkable is that his corresponding estimate of the enhanced tax yield from raising the main Corporation Tax rate by 6% - at c£16bn extra a year for the Treasury by 2024/25 – is roughly 4 times George Osborne’s estimates of the corresponding aggregate cost of reducing the Corporation Tax rate by 6%. It is difficult to see how both claims can be right. Our economy has not quadrupled in size, in the last decade (although there will be some difference due to the change in Marginal Rate bands, etc.)

So Mr. Sunak is not a “true believer”, or adherent to the theory that low taxes will boost net revenues.

Conclusion

Based on this admittedly very rough appraisal, the argument that one can reduce tax rates, from recent levels, to increase effective tax receipts, would appear to be little more than cant.

The apparent increase in Corporation Tax receipts is largely attributable to inflation over the last decade or so - and additional levies such as the Bank Surcharge.

Reducing Corporation Tax rates has in fact reduced Corporation Tax yield (even Gorgeous George admitted that would happen, when the cuts were originally announced) although it has slowly recovered – to an extent.

That is not to say that there was no logic at all to the idea that, if a tax rate is too severe, it might ultimately discourage the underlying activity that is being taxed. But that logic assumes that there is a single “golden tax rate”, that applies fairly uniformly across the population, and consistently over time. (Else it is useless, and too fragmented/ephemeral for sound government policy).

Simply put, it would seem that the pivotal Corporation Tax rate would be comfortably higher than we have seen over the last couple of decades.

If the proposed reversal of Corporation Tax rates announced in March 2021 is indeed the tacit acknowledgement of strategic tax policy failure that it appears to be, I look forward to seeing the corresponding reversal of the dividend taxation rates hike from April 2016, that must surely follow…

Please register or log in to add comments.

Interesting analysis of the relationship between tax rates and yield. Thoughtful discussion like this helps business owners think strategically, and professional input from firms like Allenby Accountants can support informed tax planning.